Often, I find it frustrating to write about software companies because, frankly, there isn’t much to dig into. Software companies typically don’t have substantial assets in terms of property, plants, and equipment (PP&E). After covering the basics of what they do, along with their financial strength and performance, that’s often it. It doesn’t satisfy my itch for a deeper analysis. However, today with Valero, that itch is thoroughly scratched. Energy companies have vast PP&E holdings, and the logistics involved in transporting and refining crude oil are far more complex than simply distributing software over the internet. There’s also a little-known fact that most people overlook: a future without oil is being pioneered by energy companies—specifically, the oil refiners, not environmental groups.

I’ll be discussing the future of energy quite a bit, even though the lion’s share of Valero’s profits currently comes from traditional oil refining. This aligns with my dialectical approach to investing. While I always have a long-term buy-and-hold mindset, I don’t always behave that way. In fact, as I’ve mentioned before, I find blind buy-and-hold strategies rather dumb. However, I do believe in having a long-term perspective, even if I decide to sell in the short term if it becomes profitable to do so.

There are a few reasons why I traditionally steer clear of energy companies. First, their profits are closely tied to the price of oil, which no single entity can fully control. If, for instance, Israel were to bomb Iran’s oil facilities, it would likely drive oil prices higher. The global lockdowns during the COVID-19 hysteria sent oil prices negative for about 48 hours. Valero has no control over such events, yet they significantly impact its business. This volatility is a key reason I generally avoid the basic materials and energy sectors.

Then there’s another reason, which may sound unusual: one day, the world will run out of oil. Why would I invest in something that’s bound to run dry eventually? Granted, that may be several decades away, and there’s certainly money to be made in the interim, but I still see energy companies as traveling down a dead-end road.

This is partly why I’ll focus disproportionately on the non-oil refining side of Valero’s business. I view it as the future of the energy industry as we inevitably enter a post-oil world. If an energy company isn’t preparing for that transition, I have zero interest in it. Valero, however, is expanding its operations into renewable diesel, ethanol, hydrogen, and carbon capture.

Finally, I want to clarify that I’m not personally concerned with global warming. Just as I wasn’t bothered about investing in the aerospace and defense industry. I have no moral objections to fossil fuels. Fossil fuels drove the rise of modern civilization and are directly responsible for the comforts of modern life. All of that would disappear if I could magically make all the world’s crude oil, natural gas, and coal vanish. It’s also worth noting that Valero is largely a U.S.-based corporation. While China is the world’s largest carbon emitter and the United States is second, this statistic can be misleading. Both the U.S. and China are large countries, whereas Europe is a fragmented mix of smaller nations. When comparing North America directly to Europe, North America emits only 1% more carbon—a difference that falls within the margin of error and is close enough to consider the two regions nearly equivalent.

https://ourworldindata.org/annual-co2-emissions

I only bring this up to point out that global warming is a global problem. Having a crusade against domestic companies will do nothing to stop it. In fact, it is better to invest in an American energy company, as they must comply with some of the toughest environmental regulations in the world. I can promise you that energy companies in the Middle East, Russia, or China are much worse environmental offenders.

So, if you have a moral qualm against profiting from the energy sector and fossil fuels, this would be the point at which to stop reading. I do not, and I intend to profit handsomely from my pragmatism. Interestingly, energy companies are also the ones most heavily invested in carbon capture technology, which anyone concerned about global warming should support.

Anyway, I’ve got about seven pages of notes to go through so here are the links to the 10-k and the most recent investors presentation:

As per the usual if I reference I page number, I am referring to the literal number on the page of the 10-k, not the page number the pdf reader states.

Let’s start with some bullet points from the investors presentation:

Operational efficiency, one of the lowest cost producers in the industry.

1.2 Billion Gallons of annual renewable diesel capacity.

12 Ethanol plants, 1.6 Billion gallons of ethanol production capacity annually.

Ratable Wholesale supply of 1.5 Billion barrels a day.

Not a vertically integrated operation.

Sustainable aviation fuel - page 10.

Carbon capture - page 11.

Classic refining very much the core of the business - page 12.

Renewable Hydrogen - page 14.

Valero states renewable diesel has fewer emissions than an EV - page 38.

From the investor presentation, I was left with more questions than anything else, as I usually am. Those presentations provide a nice summary of what's going on with visual aids, but they are very light on specifics. That’s where the 10-K comes into play. As I mentioned before, oil refining is still the core business and extremely important, but for the long term, I’m interested in Valero’s other energy products.

Connecting a carbon capture facility to their ethanol plants to create zero-emission ethanol is very intriguing. There is also the business opportunity of getting paid by other corporations to capture carbon so others can claim the net zero mantle as well. I think there are too many inherent issues with batteries for EVs to ever fully replace internal combustion engines, so zero-emission ethanol is an interesting idea. The scale of their renewable diesel operations is also music to my ears. Renewable hydrogen is another area I wanted to learn more about after reading the investor presentation. Most people probably don’t realize this, but Toyota has a hydrogen fuel cell car on the market in California and is working with Chevron to build a network of hydrogen fueling stations. I would bet on this being the future, not EVs.

But I need a lot more in the way of details. Now let’s refer to the 10-k:

Page 72 Balance sheet - no red flags, cash and short term investments + receivables > accounts payable. Very few liabilities about half of which are current liabilities.

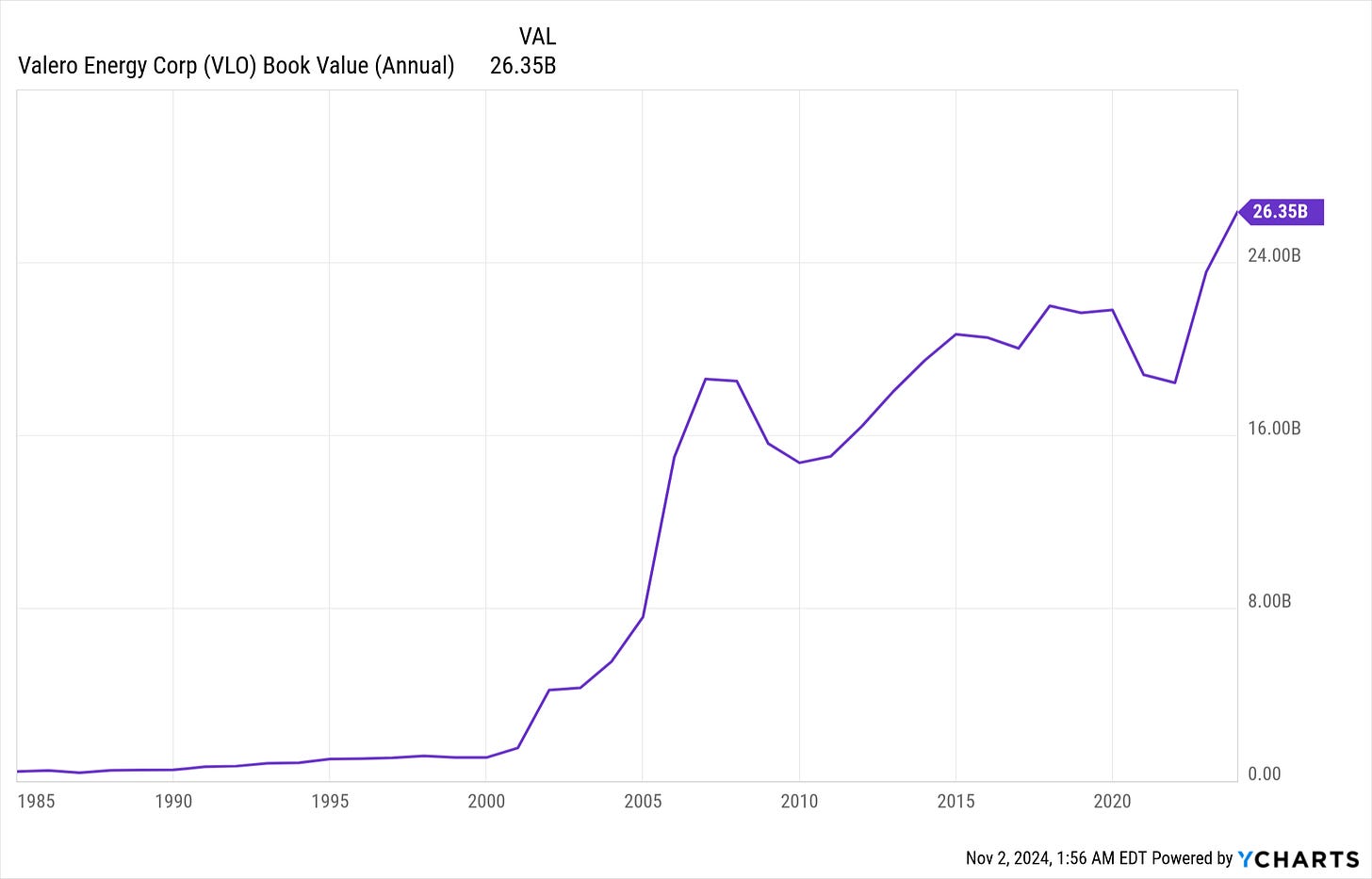

Growing equity:

Very low debt to equity ratio:

Page 73 Income statement - nothing noteworthy.

Page 76 Cash flow statement - There a bunch of references to VIEs which is unusual. However, it doesn’t seem to be a big part of the overall operation purely by the numbers.

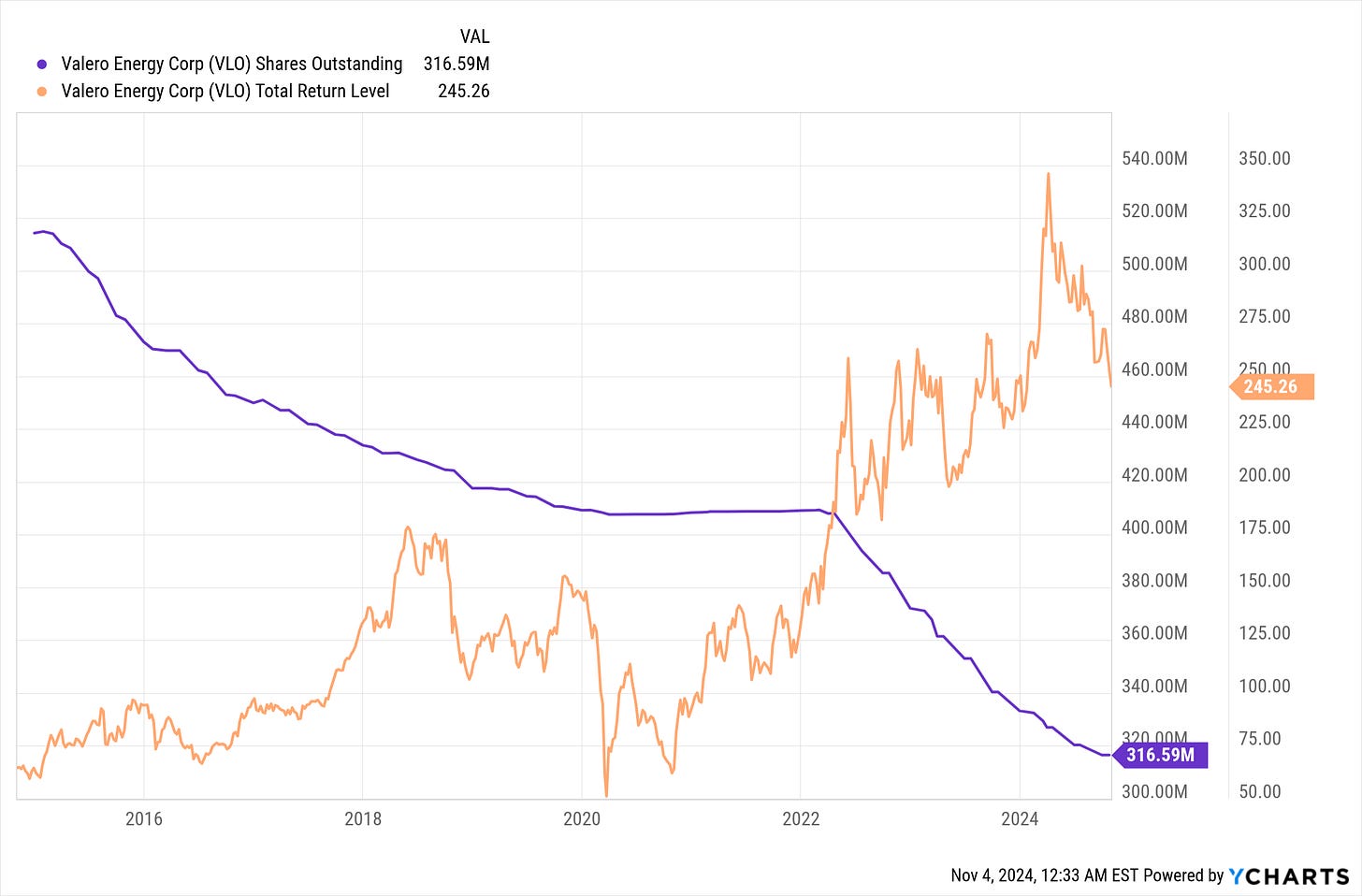

In 2023: $5.1 Billion in share buybacks.

$1.4 Billion in dividends.

For a total of $6.5 Billion in cash returned to shareholders.

With $9.2 Billion in cash from operations that leaves Valero $2.7 Billion in cash flow to maintain and grow its operations. Valero is a very profitable business that throws off a lot of cash and management is doing a good job of returning that money to shareholders.

More importantly, they are not doing so negligently. It is common for me to come across businesses where the amount of new debt they are taking on is equal to the amount of cash management is returning to shareholders. I cannot overstate how stupid this behavior is from corporate CEOs—handing out money the business doesn’t have to shareholders. Needless to say, Valero isn’t doing this. If they had a sudden and unexpected need for cash, they have an extra $6.5 billion they are returning to shareholders that they could tap into. I would much rather see a dividend cut than a business failing.

As previously stated there is a high amount of Free Cash Flow:

Page 91 - 65% of PP&E is in traditional oil refineries.

$34 Billion in oil refineries.

$5.9 Billion in oil transportation and terminals.

$3.2 Billion in renewable diesel facilities.

$1 Billion in Ethanol facilities.

Valero is diversifying but is still very much a traditional oil refiner.

Page 94 - $11 Billion in total debt and lease obligations. Well structured debt, no debt bombs in the future where a huge amount comes due at once.

Page 116 - not much stock based compensation which I like. When management pays employees or even worse, executives, with stock it can serve as incentive alignment. But the downside is the shareholders are paying the person not the corporation. Since they are diluting down everyone’s ownership stake.

Page 125 - Revenue by segment:

$136.4 Billion from oil refining.

$3.8 Billion from renewable diesel.

$4.4 Billion from ethanol.

As I said before, oil refining is still very much the hero of the story here.

Page 129 - Half of refining revenue comes from distillates and the other half is gasoline.

Page 50 - The primary distillate is diesel.

Page 46 and 49 managements discussion of segment revenue and the impact of commodity prices.

Page 52 - Lower corn prices led to a $618 million increase in revenue from ethanol. The increase was 16% of total revenue from ethanol.

Page 58 $1.9 Billion in investments in Valero’s business. Both to maintain current operations and investments into grow the business.

Page 60 detailed breakdown of capital investments.

$1.9 Billion in capex scheduled for 2024, and $1.7 Billion in capex occurred in 2023. (Remember this is the 10-k for 2023. Since 2024 isn’t over yet an annual report can’t be released with the results for the year.)

In 2024 $1.5 Billion of the $1.9 Billion is allocated toward maintaining refining operations. The rest is allocated towards growth investments.

Of the growth investments renewable diesel is getting $430 Million with a small portion toward maintenance of renewable diesel operations.

Ethanol gets a mere $60 Million in capex.

Remember in the investor presentation how renewable energy stuff is splattered everywhere and it looks like a big deal. Well, the numbers show over and over again the oil refining is still the main focus and everything else is somewhat of an after thought. At least in terms of PP&E and revenue.

Page 106 an explanation of what VIE is, which is a term all over their financial statements. It isn’t that interesting, it is just accounting for the impact of businesses they have a variable interest in and benefit from. Such as a joint venture that is distinct from there purely independent business operations.

After reading the investor presentation from May 2024 I was interested in their carbon capture investments. In this 10-k from 2023 the only mention of carbon capture is on page 5 when Valero states that they were invested in a project before it was cancelled. This was a pipeline that was supposed to be developed by Navigator Energy Services.

Now, I am not someone that views corporations as lying boogeymen. So I was curious, bit more about this new carbon capture project that Valero has cooking.

The Navigator project was cancelled in October 2023, and the Summit deal was announced in March 2024. Valero is certainly serious about expanding their operations beyond pure oil refining. This is why I’m not perturbed by the mismatch between how much Valero talks about expanding their operations and the reality of where they currently are. I don’t think it’s empty talk on Valero’s part, and as time goes on, their energy business will become more diversified.

When reading about energy companies, it’s important to be familiar with the terms Upstream, Midstream, and Downstream. Upstream refers to the early phase of the oil refining process, such as drilling. Midstream involves transportation and refining. Downstream refers to the sale of products, gas stations, etc.

Valero does not have full vertical integration. They have midstream and downstream operations, but they do not conduct their own oil drilling. In fact, the word “drilling” never appears in their 2023 10-K. This is a vulnerability in their business. However, the reason I am not invested in vertically integrated businesses like Chevron or Exxon is because Valero crushes them in terms of performance.

There is a trade-off here; oil drilling is a very expensive process. Identifying where oil reserves are underground is not always easy, and extracting crude oil from the ground is very costly. As you can imagine, building an oil rig isn’t exactly cheap. I suspect this is the performance edge that midstream processors have over their fully integrated peers. In Valero’s case, all the debt associated with the drilling process and the low margins are on the books of the businesses they buy the oil from, allowing Valero, in essence, to have a free lunch. However, there is a trade-off here: if oil reserves become scarce, the balance of power will shift back to the drilling companies, and Valero’s party will be over. Chevron and Exxon have more control over their fate, but both of them underperform the S&P 500. Valero doesn’t—the only time Valero lagged behind the S&P 500 was in 2020 and the years thereafter.

This leads to a point I want to keep hammering home: energy companies are vulnerable to swings in oil prices. This can be both good and bad; as I mentioned before, Valero had a surge in ethanol earnings because the price of corn went down. But in 2020, they took a hit when the price of oil collapsed during the COVID lockdowns. Investing is a complicated game, as nothing is ever as it seems.

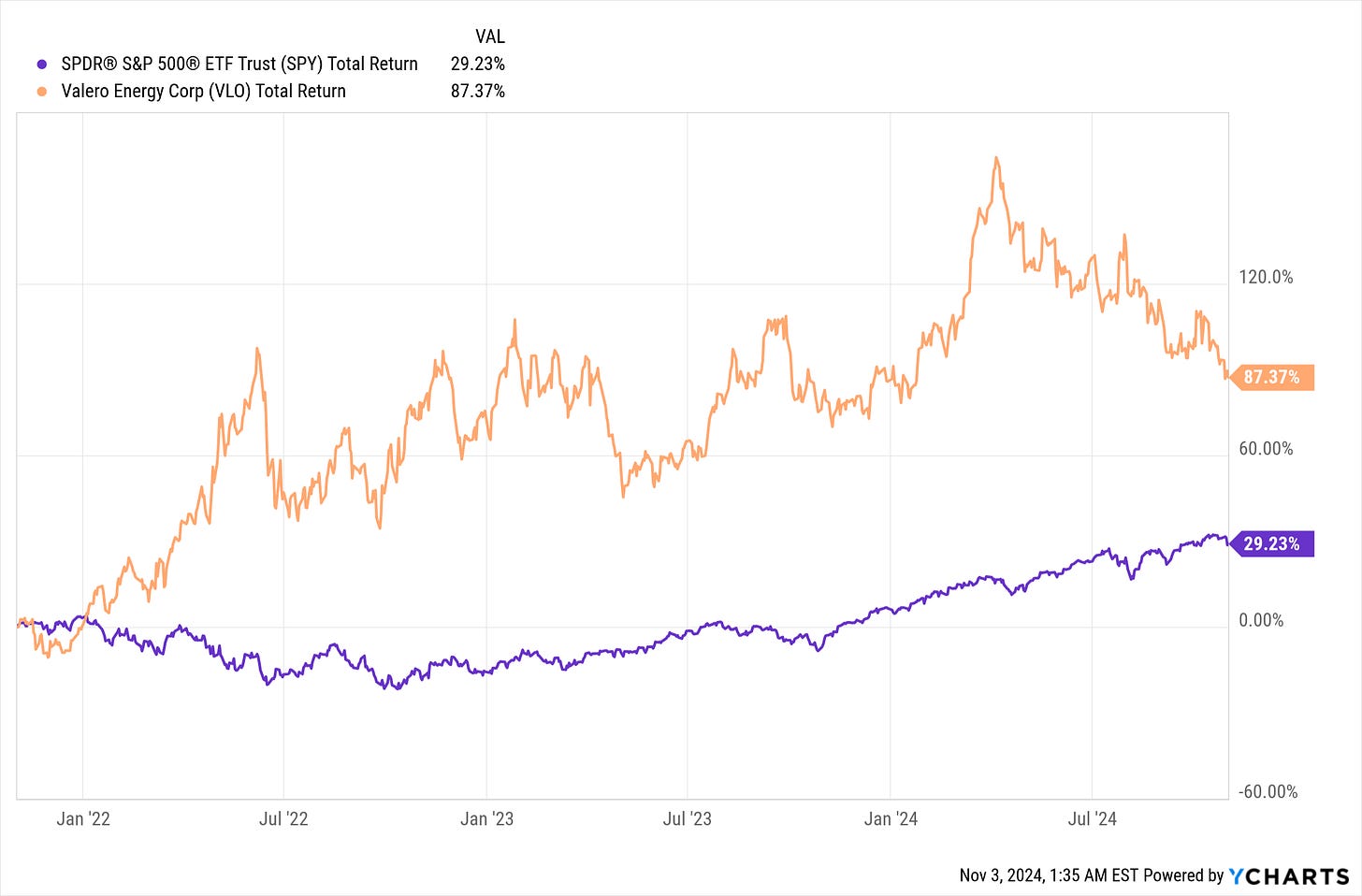

Valero vs. S&P 500 when oil was at an all time low:

I made money after investing in energy companies when the price of oil collapsed. The world wasn’t going to stay locked down forever. Only people who were short-sighted or had a very short-term focus were selling. Above is the performance of an investment in Valero vs. the S&P 500 at the all-time low in oil prices. Valero bounced back in a big way, and charts like this make me think twice about having sold before 2022. But I never have the expectation that I will perfectly predict the future or time the exact high point of a stock.

So, I’ve talked a lot about what Valero does and what is going in their business. Now lets get to all the charts:

Valero vs. S&P 500 over the last year:

Valero vs. S&P 500 over the last three years:

Valero vs. S&P 500 over the last five years:

Valero vs. The S&P 500 over the last 10 years:

Valero vs. The S&P 500 as back as I have data:

The five-year chart looks rough because it captures the period just before the price of oil collapsed in 2020. Needless to say, if you invested in an energy company in early 2020, the public’s massive freak-out about COVID completely screwed your investment. The COVID tantrum is also why the 10-year performance of Valero isn’t as impressive as it could have been. But this is the volatility inherent in the energy sector. Unexpected events can be both good and bad for the industry, and the industry has zero control over them. This is why I focus on corporations that are financially sound—so when the black swan event arrives, the business can survive the storm.

What I don’t have is a chart showing the return an investor would have gotten if they had the misfortune of investing in early 2020 but then realized they needed to double down as the price of oil collapsed. That total return there would very likely have still beaten the market, as it would be somewhere between the five-year chart and the chart showing an investment when the price of oil was at an all-time low.

Moving on…

Here’s the negative correlation that I like so much:

Dividend history:

Everything here is right on track in terms of Valero’s performance and I have already addressed the impact of the COVID lock downs. But there is one more point to discuss, the decline in revenue over the last year. Well the explanation is simple:

The price of oil has been dropping, impacting Valero’s revenue. This is an inherent part of any business that deals in a commodity as opposed to a product; they live and die by the fortune of the commodity they produce. I’m definitely repeating myself here, but the price of oil is far out of Valero’s control. However, this dip in market cap is what makes Valero an attractive investment, as it can currently be bought at a reasonable price with a PE ratio of 11.5. I’m not in the business of making precise macroeconomic predictions about the price of oil, but I will say I see zero reason to think global demand for oil is waning.

It’s an irony of hostile government regulation around energy companies. Western nations rose to their current status and enjoy all the comforts of modern life by using fossil fuels, yet we’re going to turn around and tell developing nations that, although we industrialized using fossil fuels, they can’t. Again, I don’t see global demand for oil going down anytime soon. But who knows maybe we’ll see people driving Prius Prime’s in Costa Rica.

It’s always important to consider the other person in the trade. If I’m buying stock, someone is selling it. Usually, it’s a market maker earning money on the spread, but I always pretend that isn’t the case and that I’m getting the stock directly from someone who thinks it isn’t worth owning. Why wouldn’t someone want Valero? Perhaps they’re bearish on global demand for oil or think tech stocks are the best play right now. Perhaps, they are enticed by a vertically integrated oil refiner even though drilling drags down their margins. I could keep speculating, but nothing stands out to me as a serious cause for alarm. I think the chances that I have missed something big here are as close to zero as they can be. I am getting the better of whoever it is that sold to me.

So, what is my investing edge here? Well, I don’t think many people realize that most investment in renewable energy is coming from companies that refine oil. I also don’t have any neurotic, climate-change-based reason for refusing to own stock in an energy company. Also, for what it’s worth, I live about a mile from an oil refinery and know a lot of people who work there. I know many specifics about how crude oil becomes gasoline. Oil refineries are very complex, require a lot of expensive maintenance, and even more money to build from scratch. Most oil refineries in the world still run on Visual Basic, and it’s unlikely to change anytime soon. Since refineries are so expensive to operate, energy companies do everything in their power to run them 24/7/365. Then, once or twice a year, they perform a “turnaround,” where they completely shut the plant down, and all the workers pull 16-hour shifts until the plant is up and running again. Certain maintenance just can’t be done while a plant is operational. Since oil refineries run nearly 100% of the time, this is why they all run on horribly outdated computer software. Shutting down the entire plant for weeks to install, implement, and debug a new computer system would not be acceptable. Needless to say, there is a huge barrier to entry for any new energy company attempting to gain market share.

Hamilton Helmer's 7 powers:

(The best description of Moat I have ever found.)

Scale Economies: Achieving lower unit costs through increased production, allowing a company to offer products or services at more competitive prices.

I don’t think a scale economy exists between established energy companies. The established players all have the same scale. That being said, there would be a substantial barrier to entry for any aspiring oil refiners out there. But when you think of a startup business, you don’t think of oil refining.

Network Economies: Enhancing the value of a product or service as more users join, creating a network effect that can deter competitors.

Nope, nada. Gasoline is pretty much the same no matter who produces it. Gasoline as a substance might have a network effect but the energy companies that produce it do not.

Counter-Positioning: Introducing a new, superior business model that incumbents are reluctant to adopt due to potential harm to their existing operations.

I think there is an element of counter-positioning present with Valero. They are not a fully vertically integrated oil refiner. There is a vulnerability there since they must buy crude oil from others. But Valero doesn’t bear any of the risk or expense of locating and drilling for oil and it is quite difficult and costly. If you don’t believe me read about the fight between Chevron and Exxon right now over the Hess acquisition.

Essentially, Shell and Exxon had been drilling empty oil wells off of coast of Guyana where there was thought to be a massive oil reserve. Shell gets annoyed and sells out their stake to Hess. After this point Hess and Exxon strike the motherlode. Hess can’t sell its stake in the oil field without allowing Exxon to buy it first. Chevron gets around this by just buying all of Hess. Exxon then files a ridiculous lawsuit saying the ownership contract over the oil field gives Exxon veto power over any Hess merger / buyout, which is moronic.

Anyway, the point of bringing all of that it is to show that locating and drilling for oil is very difficult and expensive. As well as being hotly contested, Valero skips all this expensive bullshit by sticking to the midstream and downstream parts of the production and refining process. It’s a trade off for sure, but currently it is serving Valero well.

Switching Costs: Creating barriers for customers to switch to competitors by making the transition costly or inconvenient, thereby fostering customer loyalty.

Nope switching where you buy gas or diesel has zero cost on the consumer.

Branding: Building a strong brand that commands customer loyalty and allows for premium pricing due to perceived value and trust.

I don’t think branding matters much for gasoline. There is such a thing as top-tier gasoline and its the only kind I put into my car engine. But most people don’t know what that is or why one would want to use it. Mostly you hear people that are fixated on finding the cheapest and by default lowest quality gasoline they can put in their car.

Cornered Resource: Securing exclusive access to a valuable asset or resource that competitors cannot easily replicate or obtain.

It could be said that perhaps Chevron, Aramco, Exxon, and all the other companies that have rights to oil fields have a cornered resource. But Valero doesn’t own any oil fields and oil is still plentiful enough that owning an oil field isn’t this mind bendingly large advantage.

Process Power: Developing unique organizational processes that enhance efficiency or quality, which are difficult for competitors to imitate.

I would argue that Valero does have process power. By opting to stay out of the oil drilling game they are laser focused on the production process. They are one of the lowest cost refiners on the planet. However, this isn’t a massive advantage. Toyota has process power but they also produce the worlds most reliable vehicles, but this is not the case when refining oil. Valero has process power yes, but it is very mild since it can only lead to cost efficiencies and not a superior product.

Well, that’s it.

It’s kind of a bummer I didn’t get this out before the election. I started writing it prior to Trump getting elected but I was dragging my feet on the editing. Valero bounced 5% today and Trump being in office certainly entails a favorable regulatory environment for energy companies. This investment just got better for at least the next four years.

My Portfolio:

FI, ADP, MCD, AFL, VLO, ITB, PPA, MOAT

*Disclaimer*

You can and will lose money in the stock market. You can lose all of your money. I can and will be wrong. I have been wrong in the past. I have lost money in the past. Investing in stocks is risky and should never be considered safe. Invest at your own risk.